PBS recently featured the new Ken Burns documentary about Earnest Hemingway. I always enjoy whatever Ken Burns produces, but I especially enjoyed this one. I’ve read about Hemingway more than other authors, but seeing the photos and film, hearing the stories, and seeing the progression of his life was fascinating. The documentary did an especially nice job handling the ten years leading up to his suicide, showing the consequences of the several head injuries he had suffered, and the family trait towards mental illness. There is a book titled Hemingway’s Boat, by Paul Hendrickson. It is a fascinating read, and, though explicitly not a biography, it is a detailed examination of Hemingway’s life from the first week of April 1934 (when he first saw the boat at the shipyard) and the first week of July 1961 (when he killed himself), all from the viewpoint of his custom-built thirty-seven foot, dual-engined, two-cabined, sea-going fishing boat that he bought from the Wheeler Shipyard in Brooklyn, New York, and christened the Pilar. Interviewing and gathering stories from people, dead or alive, including Hemingway’s wives, children, friends, guests, and shipmates who went adventuring and deep-sea fishing on the Pilar, Hendrickson gives a detailed journey of the boat’s influence on Hemingway. There are several people whose names never make into regular Hemingway biographies, and hearing the stories of their involvement with Hemingway gives a richer and more extensive picture than the typical biographies. His boat was the one thing in his life that never failed him, was always there for him, and gave him a distinctive platform for displaying his true self. “A man who let his own insides get eaten out by the diseases of fame had dreamed new books on this boat. He’d taught his sons to reel in something that feels like Moby Dick on this boat. He’d accidentally shot himself in both legs on this boat. He’d fallen drunk from the flying bridge on this boat. He’d written achy, generous, uplifting, poetic letters on this boat. He’d propositioned women on this boat. He’d hunted German subs on this boat. He’d saved guests and family members from shark attack on this boat. He’d acted like a boor and a bully and an overly competitive jerk on this boat. She’d been intimately his, and he hers, for twenty-seven years—which were his final twenty-seven years. She’d lasted through three wives, the Nobel Prize, and all his ruin. He’d owned her, fished her, worked her, rode her, from the waters of Key West to the Bahamas to the Dry Tortugas to the north coast and archipelagoes of Cuba. She wasn’t a figment or a dream or a literary theory or somebody’s psychosexual interpretation—she was actual.” Hendrickson, in May of 2005, found the Pilar sitting up on concrete blocks under a gigantic plastic-roofed carport on what was the tennis court at the Finca Vigia, Hemingway’s famous house in the hills above Havana, Cuba. Though part of the museum created out of the house and grounds, it appeared abandoned and had suffered significantly from the weather. On September 17, 1955, at his Havana home, Hemingway set down on a sheet of onionskin letterhead stationery a last will and testament in which he left his entire estate and property to his fourth wife, Mary, and nothing to his children; he expected her to provide for them according to written instructions he had given her. In August of 1961, roughly eight weeks after his suicide, Mary gave Pilar to Gregorio Fuentes, a Cuban who had served as first mate aboard the boat from 1938 and who would not die until 2002, at almost 105. The previous first mate was Carlos Gutierrez, who told Hemingway a real-life story of an old fisherman who had been out on the sea, alone, and had caught a monster marlin after a two-day battle. The marlin was so big that the fisherman lashed him alongside his skiff, but, by the time he made it back home, sharks had eaten most of it. Fuentes kept it in Cojimar for several years, then gave it to the Revolutionary Government, who moved it to Finca Vigia as the centerpiece of a Hemingway Museum. During the following years, there were attempts at preservation and restoration, but it was a hodgepodge of efforts. In 2005, when Hendrickson saw it, and, when the guards weren’t looking, touched it, the boat was in sad shape. It also had marked differences between the descriptions of the original and what was then sitting on the tennis court, feeding rumors that a duplicate boat had been built and substituted for the real thing. The official documentation of Pilar’s life was muddled and sometimes full of errors, which reflected the boat’s poor shape and its inadequate preservation. In June 2005 Finca Vigia was named to the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s list of America’s 11 Most Endangered Historic Places, even though Hemingway’s previous home was not in America, and, in 2006, was listed on the World Monuments Watch of the 100 Most Endangered Sites on the globe. Perhaps because of that criticism, the next year, the Cuban government provided funds for a complete restoration of Pilar, to be done by preservation experts at Marina Hemingway in Havana. It was done, and done well, and Pilar is now “as shiny as a new penny”, according to Dana Hewson, a member of the Boston-based Finca Vigia Foundation, a private group that provides financial assistance to efforts directed at preserving Finca Vigia. Hendrickson’s portrayal of the role that Pilar played in Hemingway’s life is wonderfully done in counterpoint to the typical biographies of his life. The stories of her regular voyages out to sea, the special trips during the war, the fishing with his children, the fascinating guests (including Karen Blixen, who authored Out of Africa)—all add dimensions that give remarkable insights to the how and why of what Hemingway did.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

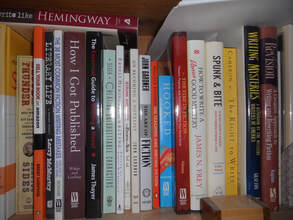

AuthorDon Willerton has been a reader all his life and yearns to write words like the authors he has read. He's working hard at it and invites others to share their experiences. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed